Cutaneous leishmaniasis: Signs, Treatment, and Prevention

Cutaneous leishmaniasis is a skin infection caused by Leishmania parasites spread by sandflies. It often starts as a small bump after a bite and can become a slow-healing ulcer. The appearance and risk depend on the species — some cause a single small sore, others multiple lesions, and a few New World species can spread to mucous membranes if not treated.

Recognizing it early matters. Typical signs include a painless or slightly tender nodule that later breaks down into a crater-like sore with raised edges. Lesions may grow over weeks to months. If you have a non-healing sore after travel to parts of Latin America, the Middle East, Africa, or South Asia, tell your clinician about the travel history — that clue is often the key to diagnosis.

How it's diagnosed

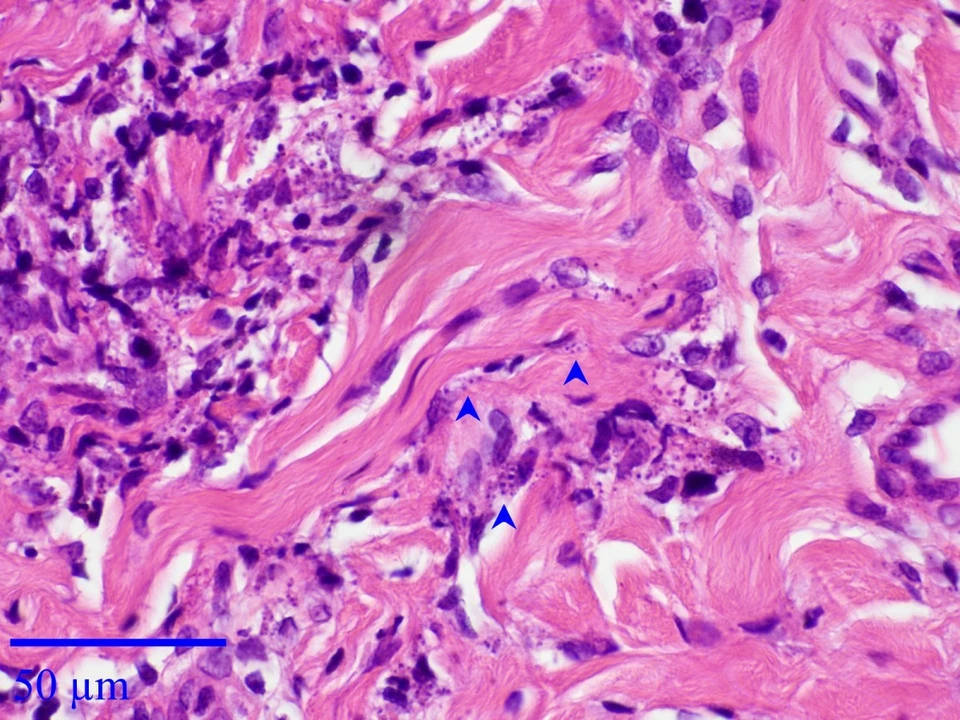

Doctors confirm cutaneous leishmaniasis with a skin sample. Common methods include microscopic smear, biopsy, and PCR testing to identify the parasite species. In some regions a leishmanin (Montenegro) skin test helps show past exposure, but it doesn't tell if the current sore is active. Accurate species ID matters because it influences treatment choices and the risk of mucosal disease.

Treatment and prevention

Treatment choices vary by species, disease severity, and where you live. Small, simple lesions may be treated with topical medicines or local measures like cryotherapy. Larger or multiple wounds often need systemic drugs — options include oral miltefosine, injectable antimonial medicines in some regions, and liposomal amphotericin for resistant or severe cases. Your provider will weigh benefits and side effects and may refer you to tropical medicine specialists.

Good wound care speeds healing. Keep the area clean, avoid unproven ointments that can mask infection, and watch for signs of bacterial infection such as increased pain, pus, or fever. If a secondary infection develops, antibiotics may be needed.

Prevention focuses on avoiding sandfly bites. Use insect repellent containing DEET or picaridin, sleep under insecticide-treated nets, wear long sleeves and pants at dusk and dawn, and choose accommodations with screens or air conditioning. If you live in or travel to endemic areas, learn local peak sandfly times and avoid outdoor activity then.

When to get help: seek medical care for any skin sore that won’t heal in a few weeks, especially after travel to endemic areas. Early testing reduces the chance of complications and scarring. If you have lesions in the nose or mouth region after travel to the Americas, ask specifically about species that can cause mucosal spread — that situation needs prompt attention.

Research into vaccines and safer oral medicines is ongoing, but prevention and early treatment are the best tools now. If you need help finding a tropical medicine clinic or interpreting test results, a local infectious disease specialist or travel medicine service can guide you.

Keep copies of travel records and photos of lesions — they help doctors track progress. Always tell your provider about any animal exposures or insect bites during travel. Early action saves skin and time.

The Use of Fusidic Acid in the Management of Cutaneous Leishmaniasis

I recently came across an interesting study about the use of fusidic acid in managing cutaneous leishmaniasis. For those who may not know, cutaneous leishmaniasis is a parasitic skin infection that can cause severe skin lesions. Fusidic acid, commonly used for bacterial skin infections, has shown promise in treating this condition. The research indicates that it can be an effective and safe alternative to traditional treatments. This is great news for those affected by this infection, as it offers a new option for management and recovery.

About

Skin Care and Dermatology

Latest Posts

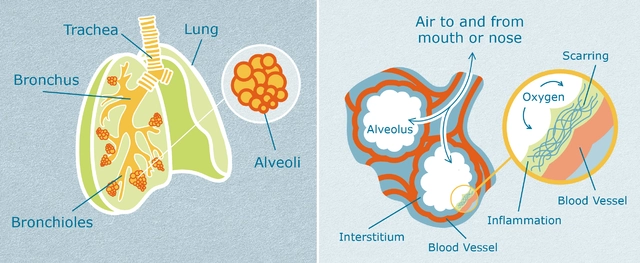

The Impact of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis on Relationships and Social Life

By Marcel Kornblum Apr 30, 2023

Discover Top Levitra Discounts and Deals for Your Health

By Marcel Kornblum Dec 28, 2024

Unlock the Power of Jojoba: The Ultimate Dietary Supplement for Health and Wellness

By Marcel Kornblum May 27, 2023