When a pregnant person takes a medication, it doesn’t just stay in their body. It crosses the placenta - a living, breathing organ that connects mother and baby - and enters the fetal bloodstream. This isn’t science fiction. It’s biology. And it happens with every pill, injection, or patch used during pregnancy. The question isn’t whether drugs get to the baby, but how much, how fast, and what kind of impact they have.

The Placenta Isn’t a Wall - It’s a Gatekeeper

Many assume the placenta acts like a shield, blocking harmful substances. That’s a myth. The placenta is more like a bouncer at a club: it lets some things through, blocks others, and sometimes even pushes things back out. At full term, it weighs about half a kilogram, covers an area the size of a large dinner plate, and has a surface area of 15 square meters - all designed for one purpose: exchange. It doesn’t just passively let drugs drift through. It’s packed with transport proteins that actively move substances in either direction. Two key players are P-glycoprotein (P-gp) and breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP). These are like molecular pumps that shove certain drugs back toward the mother’s blood, protecting the fetus. But if those pumps are overwhelmed or blocked, drugs flood the fetal side. For example, when scientists blocked P-gp in lab models, HIV drugs like saquinavir and lopinavir crossed into the fetal bloodstream 1.7 to 2.3 times more easily. That’s not a small change. That’s the difference between a safe dose and a dangerous one.What Makes a Drug More Likely to Reach the Baby?

Not all drugs cross the placenta the same way. Four main factors decide whether a drug gets through - and how much:- Molecular size: Drugs under 500 daltons (Da) slip through easily. Ethanol (46 Da) and nicotine (162 Da) cross almost freely. Insulin (5,808 Da)? Almost none gets through.

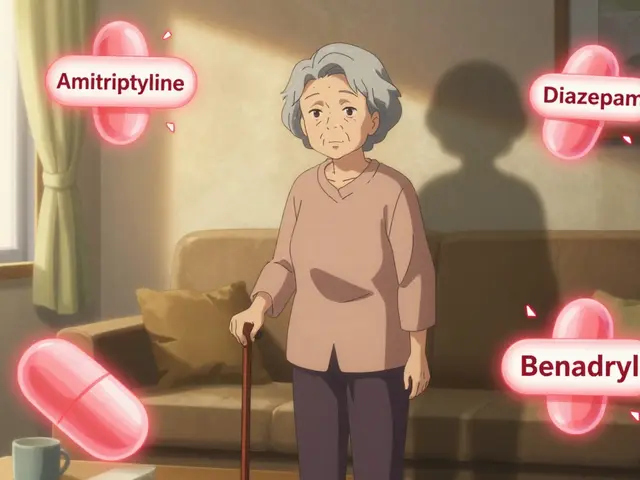

- Lipid solubility: Fatty, oil-soluble drugs slip through cell membranes like butter on toast. A log P value above 2 means high transfer. That’s why benzodiazepines and many antidepressants cross readily.

- Protein binding: Only the unbound portion of a drug can cross. Warfarin is 99% bound to proteins - so even though it’s small and fat-soluble, very little reaches the fetus.

- Ionization: At the body’s pH of 7.4, drugs that are charged (ionized) struggle to pass. Non-ionized drugs cross much faster. This is why some antibiotics and painkillers behave differently depending on maternal blood pH.

Timing Matters - The First Trimester Is the Riskiest

The placenta changes as pregnancy progresses. In the first trimester, it’s thinner, less organized, and has fewer protective transporters. That means drugs cross more easily - and faster. This is why the first 12 weeks are so critical. That’s when organs form. A drug that disrupts heart development or neural tube closure during this window can cause permanent damage. Valproic acid, used for epilepsy, crosses easily and is linked to a 10-11% risk of major birth defects - more than three times the baseline rate. By the third trimester, the placenta becomes more selective. P-gp and BCRP levels rise, acting like tighter filters. But that doesn’t mean it’s safe. Some drugs still get through in large amounts. Methadone, for example, reaches 65-75% of maternal levels in the fetus - leading to neonatal abstinence syndrome in 60-80% of exposed babies.

Real-World Examples: What Drugs Actually Do to Babies

Some medications are known risks. Others are still a mystery. Here’s what we know:- SSRIs (sertraline, fluoxetine): Cross easily. About 30% of newborns show temporary symptoms like jitteriness, feeding trouble, or breathing issues - called neonatal adaptation syndrome. These usually resolve in days.

- Antiepileptics (phenobarbital, valproic acid): Phenobarbital crosses nearly completely. Valproic acid is linked to autism, spina bifida, and facial abnormalities. Many neurologists now avoid it in pregnancy.

- Opioids (methadone, buprenorphine): High fetal exposure. Buprenorphine is slightly safer than methadone, but both cause withdrawal in newborns. The key is stable dosing - not abrupt stops.

- Chemotherapy drugs (paclitaxel, methotrexate): Paclitaxel crosses in 25-30% of cases; that number jumps to 50% if P-gp is inhibited. Methotrexate is blocked by placental transporters - but still dangerous if used in early pregnancy.

- Antibiotics (doxycycline, tetracycline): These bind to fetal bone and teeth, causing permanent discoloration. Avoided after the first trimester.

Why Animal Studies Don’t Tell the Whole Story

You might wonder: if mice and rats are used to test drug safety, why do we still get surprises? Because human and rodent placentas are built differently. Mouse placentas are 3-4 times more permeable to many drugs. A compound that looks safe in rats might be deadly in humans - or vice versa. That’s why the FDA now requires human placental tissue studies for new drugs. Lab models have improved. Scientists now use dually perfused human placentas - meaning they keep a donated placenta alive after birth and pump blood through both sides to see how drugs move. Others use placenta-on-a-chip devices: tiny silicone chips lined with human placental cells that mimic real transport. One study showed glyburide (a diabetes drug) transfer in these chips matched real tissue within 1%. Still, there’s a gap. Most studies use placentas from full-term births. But the most vulnerable period is early pregnancy - when placentas are still forming. We don’t have enough data on how drugs behave in the first 10 weeks.What’s Changing in Medicine - And Why It Matters

The thalidomide disaster of the 1960s - where babies were born with missing limbs because their mothers took the drug for morning sickness - changed everything. It led to laws requiring pregnancy safety testing before drugs hit the market. Today, the FDA requires drug labels to include specific data on placental transfer. Newer labels don’t just say “Category C” anymore. They tell you: “Cord-to-maternal concentration ratio was 0.85 in 12 healthy term placentas.” That’s progress. Pharmaceutical companies are investing more than ever. Funding for placental research jumped from $12.5 million in 2015 to nearly $48 million in 2022. Why? Because 45% of prescription drugs still lack adequate pregnancy safety data. Doctors are flying blind. New tech is emerging too. Researchers are testing nanoparticle drug carriers that could deliver medication directly to the fetus - but that’s a double-edged sword. If the nanoparticles get stuck in the placenta, they could cause inflammation or block nutrient flow.What Should You Do If You’re Pregnant and Taking Medication?

Don’t stop your meds without talking to your provider. Abruptly stopping seizure meds, antidepressants, or blood pressure drugs can be more dangerous than the drugs themselves. Here’s what to do:- Review every medication - including over-the-counter pills, herbal supplements, and topical creams. Many people don’t realize lotions or patches can enter the bloodstream.

- Ask about alternatives. Is there a safer drug? For example, buprenorphine instead of methadone for opioid use disorder.

- Check dosing. Sometimes, lowering the dose reduces fetal exposure without losing effectiveness.

- Consider timing. If you’re taking a drug that’s risky in the first trimester, your doctor might delay starting it until after week 12 - if possible.

- Use therapeutic drug monitoring. For drugs like lithium, digoxin, or anticonvulsants, blood levels can be checked to ensure you’re getting the lowest effective dose.