Race and Cancer: How Genetics, Access, and Environment Shape Outcomes

When we talk about race and cancer, the observed differences in cancer rates and survival between racial groups. Also known as cancer disparities, it isn’t about one group being more prone by DNA alone—it’s about how society, healthcare systems, and environment shape who gets diagnosed early, who gets effective treatment, and who survives. Studies from the American Cancer Society show Black men are nearly twice as likely to die from prostate cancer as white men, not because their genes are more aggressive, but because they’re less likely to get screened, less likely to see a specialist quickly, and more likely to face delays in care.

These gaps show up everywhere. Latino patients with breast cancer often get diagnosed at later stages—not because the disease spreads faster in their bodies, but because language barriers, lack of insurance, or fear of deportation keep them from getting checked. Native American communities face higher rates of liver and stomach cancers, tied to limited access to clean water, healthy food, and preventive care. Meanwhile, Asian Americans have higher rates of stomach and liver cancer linked to hepatitis B, but are less likely to be tested or vaccinated due to cultural stigma or lack of targeted outreach. These aren’t random trends. They’re the result of decades of unequal investment in communities, biased algorithms in diagnostic tools, and clinical trials that rarely include diverse populations.

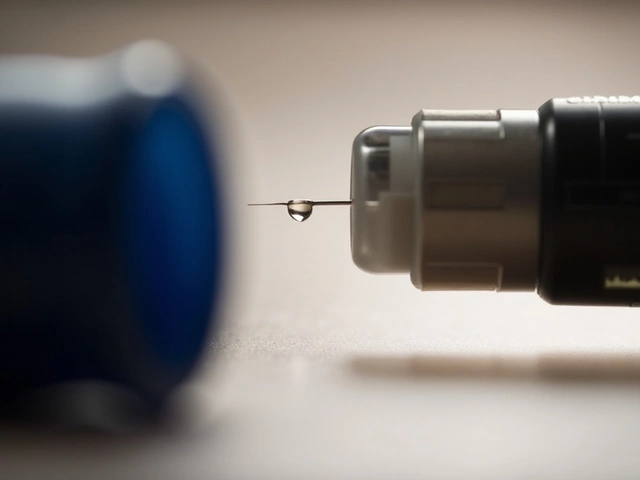

Even something as simple as a pharmacogenetic testing, using your DNA to predict how you’ll react to cancer drugs. Also known as personalized medicine can fail if it’s built only on data from white patients. A drug that works well for one group might be less effective—or more toxic—for another, simply because the research never tested it on them. That’s why knowing your family history matters, but so does knowing your access to care. And it’s why a pill that works for one person might not be the right choice for another, even if they have the same cancer type.

What you’ll find below isn’t a list of medical theories. It’s real stories from real people navigating a system that doesn’t always work for them. You’ll see how inactive ingredients, the non-active parts of pills that can trigger reactions or affect absorption. Also known as excipients sometimes cause unexpected side effects in certain populations. You’ll learn how generic drug prices, set by opaque insurance negotiations that leave patients paying more than cash. Also known as spread pricing hit low-income communities hardest. And you’ll find practical advice on how to ask the right questions, push back on delays, and get the care you deserve—no matter your background.

How Race and Ethnicity Affect Carcinoma Risk and Treatment Outcomes

Race and ethnicity significantly influence carcinoma risk, diagnosis timing, and treatment access. Learn how genetics, cultural barriers, and systemic bias affect outcomes-and what can be done to close the gap.

About

Health Conditions

Latest Posts

Eurax (Crotamiton) vs Other Anti-Itch Medications: Pros, Cons & Alternatives

By Marcel Kornblum Oct 17, 2025

How to Talk to Your Doctor About Staying on a Brand Medication

By Marcel Kornblum Dec 4, 2025

Semaglutide: A Promising Treatment for Fatty Liver Disease and More

By Marcel Kornblum Aug 17, 2024